Why do we remember the war in this way?

Our remembrance is shaped by many factors. Some have developed slowly over the 90 years since the War, others more recently (in the 1960s for example).

Dan Todman (2005) provides a lengthy list of cultural and social events which he feels has shaped the memory of the War in terms of it being perceived as futile or horrific, with needlessly excessive casualties. These include:

- the shaping of remembrance by bereaved parents to focus on the dead

- the compliance with this by the nation out of respect, thus diminishing any thoughts of celebrating a victory

- the plethora of war books in the late 1920s and 1930s which often focussed on the harsh realities of trench warfare

- attitudes in the Second World War to compare that conflict (i.e. meaningful, better led and fought) against the perceived disasters of 1914-1918

- the prominence of the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon which stressed futility, pity, suffering, the horror, incompetence

- the screening in 1964 of the BBC’s The Great War series which, scripted in part by John Terraine, presented a predominantly negative view of the war and the generals

- the publication of Alan Clark’s The Donkeys in 1961 which, though riddled with inaccuracies, cemented the view of incompetent generals

- the popularity of Joan Littlewood’s Oh! What a Lovely War (though Todman suggests this was as much a product of the accepted viewpoint that had developed in the 1960s as a shaper of attitudes), and the 1969 filmed version by Richard Attenborough

- publication of Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory in 1975, again a highly influential book, but historically inaccurate

- the screening of the BBC’s The Monocled Mutineer in 1986 which again depicted the negative side of the war

- the screening of the BBC’s Blackadder Goes Forth in 1989

- later war novels such as Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, Sebastian Faulks’s Birdsong, Susan Hill’s Strange Meeting

Todman (2005, pp. 224-226) also identifies five generations who have shaped remembrance of the war:

- The parents of those who fought and died in the conflict who exerted a powerful influence on the public in terms of focusing on the sacrifice. However, they would not have viewed the war as futile or mistaken. This generation gradually disappeared during the 1950s.

- The generation who had fought in the war and survived. Their attitudes were undoubtedly varied, and often remained hidden until the 1960s when historians began to take an interest in recording their views. However, by then their memories had possibly become blurred or shaped by what they thought people ‘expected to hear’. These veterans began to die off in the 1970s and throughout the 1980s, and only a handful remain.

- The children of those who fought in the war (born as late as the 1930s). When they became adults they were the generation who wrote the books, plays, and television series that became so popular from the 1960s onwards. They are probably the most important for shaping the ‘myth’ of the war.

- The grandchildren of those who had fought in the war. They shared memories with their grandparents in the 1960s which perpetuated the memory and shaped reactions to the war in the 1980s and 1990s.

- The great grandchildren of those who had fought in the war. For the most part they will have had no contact with veterans and have no personal connection to it, but they provided the audience for Blackadder and the readership for Birdsong.

Does this ring true to you? Does this explain how remembrance was shaped?

Now, read the following essays below before you proceed:

Previous: Exercise I Next: Exercise II

Page Notes

Spiritualism

The process of grieving is a complicated matter, and on such a massive scale as the death toll incurred in 1914-1918 it is unsurprising that not everyone could come to terms with their loss, or comprehend the separation. Conventional religions did not seem to offer enough, nor was sufficient solace found in the national acts of Remembrance.

A noted phenomenon then, during and after the war, was the remarkable growth in spiritualism – labelled, at the time, as a science. The belief that there is life after death is common to many religions, notably Christianity which was the dominant religion in Britain at the time, but spiritualism went further than that. Whilst attempting to explain the afterlife in pseudo-scientific terms, it also suggested that it was possible to contact the dead, and more interestingly (in terms of religious belief at the time which viewed such acts as heretical) it encouraged it.

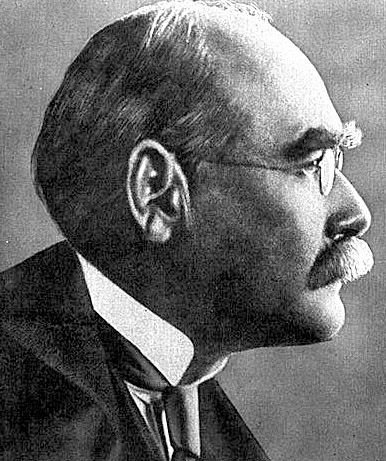

Although spiritualism had existed long before the war (indeed communicating with the dead, or attempting to goes back to Biblical times and beyond); the aftermath of the 1914-1918 conflict, and the mass grief it engendered, saw a very public rise in the popularity of mediums, séances, and similar. New ‘academic’ journals appeared and the movement attracted notable public figures such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling (who had both lost a son in the war) – though Kipling’s treatment of the subject is ambivalent at best.